“Gilded Glamour,” the dress code of the 2022 Met Gala, scheduled to take place on Monday, throws wide the doors of sartorial imagination. The reference is rather self-reflective, for one of the biggest and most exclusive fundraisers in the United States. The Gilded Age, the last thirty years or so of the nineteenth century, was characterized in the U.S. by the rise of great industrial and financial wealth for some, and increasing poverty for others. Everyday fashion for the elite was marked by excess. Electric and steam-powered looms enabled new textile varieties, synthetic dyes expanded popular color palates, and hats rose to ridiculous heights.

Although I suspect the stars of 2022 may interpret the dress code simply, as an invitation to get very, very fancy, their historical analogs—the rich people who attended balls and soirées in the late nineteenth century—dressed not just luxuriously, but oddly, with ample use of personality and humor. Think dead animals, precise copying of historical references, and the occasional flash of techno-wizardry. In case anyone with a ticket for Monday’s ball is still looking for inspiration, here are a few choice costume suggestions from balls of the era, plus one counterexample: a costume to avoid.

Miss Kate Feering Strong wore this heavily-taxidermied number to the premier New York City social event of the 1880s, Willie and Alva Vanderbilt’s 5th Avenue fancy-dress ball, which doubled as a housewarming. (The railroad-baron Russells’ party in the season finale of HBO’s The Gilded Age is based on the Vanderbilt Ball—but, disappointingly, features zero cat heads.)

In 1883, Strong’s likeness was captured by the premier photographer of the elite, Jose Maria Mora, a dapper Cuban refugee hired to record the visual details of the party. The New York Times report on the party confirms that Strong’s headdress was indeed fashioned from a “stiffened white cat’s skin,” with a tail pendant trailing behind. The blue ribbon tied around Strong’s neck like a collar has printed on it, possibly in diamonds, “PUSS”—Strong’s nickname and the inspiration for her ball apparel.

Mora almost certainly did not neglect to capture the full-length view of Strong’s costume, but I know of no surviving photograph recording the innovation of the skirt. According to the Times, “The overskirt was made entirely of white cats’ tails sewed on a dark background.” Did you ever see a skirt sewn together out of old neckties, faddish among thrift-shop devotees and Sassy Magazine subscribers, in the mid-1990s? Like that, but with cat tails.

If contemporary Gala designers like Moschino or Theophilio balk at incorporating cat parts into a design, accessorizing with most any portion of a bird would also be appropriate for the “Gilded Glamour” theme. Milliners included entire bodies of birds on towering ecosystems of hats in Great Britain and the U.S. during this period, while other designers fashioned earrings from hummingbird heads and beaks. However, many of the species whose feathers were preferred by Gilded Age gals, such as the snowy egret or great heron, are now protected by the 1918 U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act, passed in response to these turn-of-the-century hat bird massacres.

While Miss Strong’s feline fancy-dress choice was difficult to outshine at the Vanderbilt Ball, the hostess’s sister-in-law managed. Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt commissioned haute couture designer Charles Frederick Worth to create a gown inspired by the new craze: electricity. Thomas Alva Edison had just patented his light bulb the year before. This very gilded gown (you can see it in the image at the top of this page, or in color at this link) consists of golden satin overlaid on blue velvet, accented with shimmering lightning bolts and starbursts stitched in metallic beads, thread, tassels, and diamonds. Diamonds also covered the elaborate headdress. A hidden battery allowed Alice to illuminate the ensemble with the flick of a switch, a feat barely short of magic in 1883.

You might assume that kitschy-costume aficionado Katy Perry would be out of the running for this resplendent option. She already wore a lit-chandelier costume to the 2019 Met Gala, with its “Camp: Notes on Fashion” dress code, referencing Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay. But actually, doubling down would only increase the historical authenticity, as Gilded Age elite often repeated their greatest wardrobe hits, including costumes.

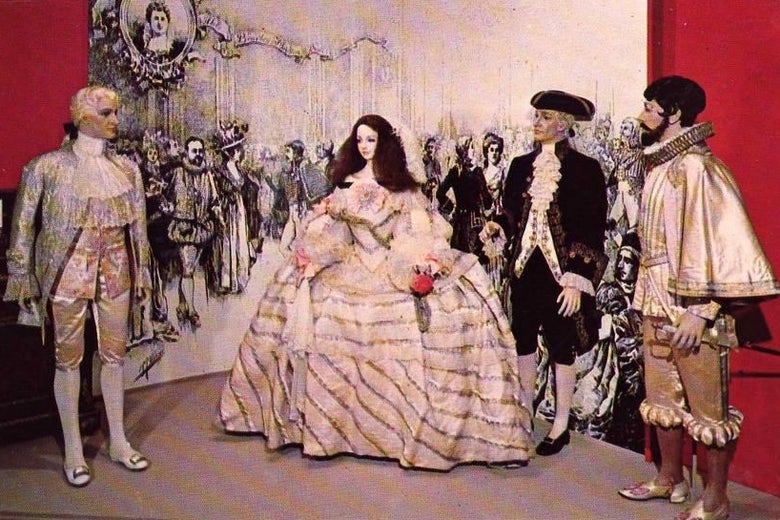

The 2022 Met Gala theme is “In America: An Anthology of Fashion.” But the spelling of the dress code, with its included “u,” evokes British and European influences. At “fancy-dress balls,” a common trope was to mimic apparel captured in renowned portraits of aristocrats of the past. For the 1897 Bradley-Martin Ball, considered “the last gasp” of the Gilded Age, the hosts claimed the event’s very short notice would stimulate the local economy, suffering amidst repeated economic upheavals blamed on volatile stock markets and irresponsible railroad investments. Despite the mere two weeks’ lead time, socialite Kate Brice managed to telegraph directives to the much-favored designer Charles Frederick Worth. Worth hurriedly copied the outfit worn by Philip IV’s daughter, the Infanta Margarita, in a 1656 painting by Diego Velasquez.

Note: when dressing from a painting, heed the warning in the 1938 gothic novel Rebecca, and be sure not to accidentally copy a costume once worn by your rich husband’s murdered first wife. How embarrassing!

Men of leisure costumed up quite as much as did the ladies. James L. Breese arrived at the Bradley-Martin Ball as a 17th-century duke, in white corded silk embroidered with pearls and silver lace and a delicate French-heeled shoe. His sword, encased in a silk scabbard, was literally gilded. Breese boasted of his outfit’s strict authenticity, but reportage on male finery was more ambivalent by the end of the century, complimenting the staid uniforms of policemen acting as security at the ball over satin, pastel-colored brocade like Breese’s. The Times asserted that the costumed men were “more disguised than the women” and poked fun at the prominent men wearing tights and jewels: “In contrast with the men who were there to guard them, these interesting and powerful gentlemen looked rather small.” Ideas of power and manhood were changing at the turn of the century. In the 1890s, the virtues accorded to manliness—restraint and studied refinement—made way for the cultural attributes of masculinity, a new term indicating strength, virility, and a disdain for feminine pursuits, including costuming. The Gilded Age was a rare opportunity for post-French-Revolution men to preen like peacocks, but that window closed quickly.

If by 1897, fewer Louis XVIs showed up to dance with the inevitable Marie Antoinettes, the men who did come to fancy-dress balls still took masquerade to heart. Law clerk Richard Welling offers an excellent example of what not to wear today, also from the Bradley-Martin Ball. Welling, on the periphery of the upper echelon, confessed to his diary that anticipation of the event made his “[b]owels shake about.” But he persisted, convincing a Natural History Museum curator and Harvard professor to provide “an authoritative drawing” of the seventeenth-century Algonquin Chief Miantonomah for Welling’s mimicry.

For two weeks, Welling was preoccupied with details—an “Indian wig,” furs and robes, necklaces, and buckskin shirt, all fretted over quite earnestly, with admissions that he did “debate with myself whether I can carry it out.” Like pretty much all examples of cultural appropriation, Welling’s outfit underscored the Gilded Age delight in white conquest over minority groups. He featured a necklace comprised of deer teeth, bear claws, shells and beads, all objects purportedly exchanged between the chief and Welling’s own ancestor, who stole land from the Algonquins in Rhode Island. Dear celebs: Unless you are a member of the Algonquin tribe yourself, this is certainly one Gilded Age costume to strike off the list.

Of course, most Gilded Age Americans were not rich, and it wasn’t only the rich who loved a masquerade. New York City’s French Ball took place at auditoriums such as the Metropolitan Opera House and Madison Square Garden from 1866 to 1901, and was just one of the premier public events held around Mardi Gras season, as aspects of New Orleans’ great event caught on in other cities. According to historian Timothy Gilfoyle, the French Ball attracted thousands of ticketed participants, from “Wall Street businessmen to prostitutes and gay drag queens.” The Times called the event “vice’s carnival.” Popular costumes here tended to reveal more of their wearers than those on 5th Avenue, including (per scandalized reports) a fairy whose costume was “principally a set of wings” and one ballerina with nothing on under her tutu. Reports of casual French Ball activities included tabletop can-can dancing.

TL:DR: Here are my suggestions for Met Gala goers who want to do something new, and historically accurate, this year: Do wear full tights, regardless of gender, unless you wish to let your balletic undercarriage breathe. Dress from famous portraits, but be certain not to imitate your date’s ex by mistake. Evoke recent technology, available only to the very rich (perhaps a rendition of Jeff Bezos’ ultra-phallic rocket?). Be sure any dead animal parts are properly treated, to avoid embarrassing odors, and that they do not belong to any protected species. When in doubt, consult Ardern Holt’s popular Fancy Dresses Described; or, what to wear to fancy-dress balls, updated regularly between 1879 and 1896 (after which point, most of high society snubbed the fancy-dress ball). And finally, even though the Gilded Age crowd fully embraced cultural appropriation, just don’t. There are limits in the pursuit of historical authenticity.

Gilded Glamour at the Met Gala: Costume ideas for celebrities going for historical accuracy. - Slate

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment